The Story Of Chuck Berry and “Maybellene”

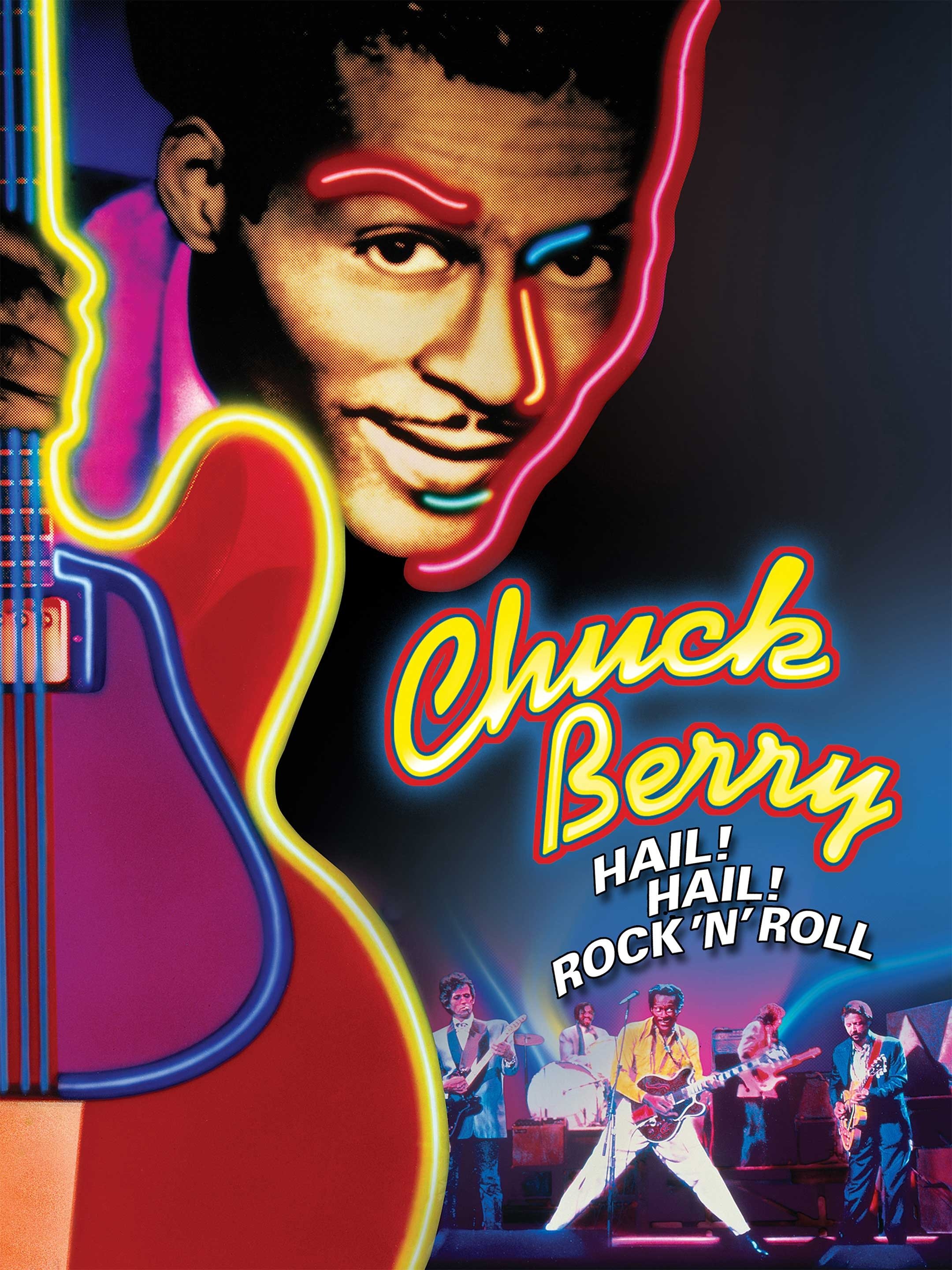

In 1955, a sort of undefined, get-you-in-the-belly music was named rock 'n' roll, though as John Lennon once put it, "If you tried to give rock 'n' roll another name, you might have called it Chuck Berry." Berry was a young man in St. Louis in 1955. He recorded the song "Maybellene" for Chess Records, and the rest is history. At a mere two minutes and 18 seconds, the song embodied the sexual tensions of a generation or, as Berry's producer put it, "the big beat, the cars and young love; it was a trend and we jumped on it." It took Chuck Berry and his band 36 tries to get "Maybellene" just right, so you can forgive him if that trademark opening guitar lick of his sounds a bit tired. In fact, it was Berry's first time in a recording studio. At 29, he'd been performing in a St. Louis trio for several years, playing mostly blues and R&B standards. But Berry had started writing his own songs, inserting elements of white country music, and he wanted to see if they would sell. On a Friday night in May 1955, Berry drove up to Chicago to catch a show by his idol, the blues great Muddy Waters. "And I listened to him for his entire set," Mr. Berry recalls. "When he was over, I went up to him, I asked him for his autograph and told him that I played guitar. 'How do you get in touch with a record company?' He said, 'Why don't you go see Leonard Chess over on 47th?'" So early Monday morning, Berry made his way to Chess Records and positioned himself in a store across the street. When Leonard Chess arrived, Berry ran over and made his pitch. Chess was impressed by the young man's self-confidence and told him to come back with a tape of his own material. Berry returned the following week, bringing with him the other members of the trio, pianist Johnnie Johnson and drummer Eddie Hardy, and four new songs. "And we set the band up, and we played all four of them," Berry says. "We don't know what they were saying; they're in the studio, and they listened." Berry thought they were listening to "Wee Wee Hours," a blues song. After all, Chess Records was known around Chicago as a blues label. But Leonard Chess was fascinated by another, more upbeat song, "Ida Mae," that Berry had adapted from a traditional country tune called "Ida Red." Chess was sure the new song could be a hit, but he didn't like the name. It was too rural, and he thought its similarity to "Ida Red" might pose copyright hassles. "And that was a problem, so nobody could think of a name," pianist Johnnie Johnson says. "We looked up on the windowsill, and there was a mascara box up there with Maybellene written on it. And Leonard Chess said, 'Why don't we name the damn thing "Maybellene"?'" That was no problem for Berry, who cared more that the beat of the song not be disturbed. "'Maybellene' has the same rhythm as 'Ida Red,' like dah-di-dah, you know, 'Maybellene,' 'Ida Red,' you know. So rhythm I had, but I had somebody else's title, you know. So that's how "Maybellene" came up." After the recording session, Berry returned to St. Louis, where he worked for his father's construction company and was studying to become a hairdresser. He and the band were now playing three nights a week, and they'd begun to draw a more diverse audience. White people were showing up to hear this strange, new mix of blues, R&B and country and western. But after several weeks, Berry still hadn't heard from Leonard Chess. He had no idea what was happening with his songs. Then one day in August, he heard it. "Passing by a tailor shop that I got my high school graduation coat made at, and I passed by the shop until the song played out, you know; I didn't want anybody to see me listening, you know, to — but it was 'Maybellene' I was listening to. And when it played out, you know, that was my last walk past the door of the place. And I flew home — you know, I was about 20 blocks from home — and told everybody, `I heard it, I heard it, I heard it. I heard me sing.' And these are relatives; these are people that live on the block. So that was the first time I heard it: that day, nice, sunny day, beautiful day. Knocked me out to hear myself, you know." Propelled by its persistent driving rhythm, "Maybellene" quickly rose to No. 1 on the R&B charts. Two weeks later, in August 1955, it hit No. 5 on the all-important pop chart. At WINS in New York, disc jockey Alan Freed played the song for two hours straight one night. And down South, a relatively unknown singer named Elvis Presley began to include the song in his own performances. Joe Edwards is the owner of Blueberry Hill, the St. Louis club where Chuck Berry still performs every month. He says Berry was not only a rock 'n' roll pioneer, he was its first great poet. "Chuck Berry was the first artist that really did it all, like wrote the songs, he wrote the lyrics of the music, he choreographed the stage show. And no one did that. Until Bob Dylan came along, there was no one that could master him, I think." It was the way his words stayed so close to the beat, yet still managed to sound like real speech. And there were the puns. From the opening line in "Maybellene" where he sang "motor-vatin'," as in "As I was motor-vatin' over the hill," Chuck Berry's clever wordplay would change rock lyrics forever. "What he did with the English language and how he worked the words and the detail that he put into the songs, I mean, if you listen to the verses in a Chuck Berry song, they keep changing, and they keep telling the story," Edwards says. "And then pretty soon, by the end of that song — and it might only be a two-minute, 58-second song — but you've heard a lifetime in the life of a teenager." Berry was also the first black rock artist to find national success performing his own music. From his experience in St. Louis, he knew what that took. And while he still listed black guitarists like Charlie Christian and T-Bone Walker as his main influences, Berry was more careful with his own image, making his diction, as he described it, harder and whiter. Johnnie Johnson remembers that this could cause problems on the road. "I mean, people that never seen it, after the record come out and such a big hit and we went on this tour, not knowing — you know, never seeing a picture or nothing of Chuck, they mistook it that Chuck was white. And we would walk out on the stage, there'd be a lot of ohs and aahs and whatever because he's a black man playing hillbilly music." Sometimes Berry didn't make it as far as the stage. Showing up for a scheduled concert one night in Knoxville, Tenn., he was turned away at the door. The show's organizers explained, "It's a country dance, and we had no idea that 'Maybellene' was recorded by a Negro man." Berry returned to his car and listened as a white replacement band played his music. And there were other unpleasant surprises. When Berry finally got his hands on a copy of the record, he saw he was listed as only one of three songwriters. Alan Freed, the disc jockey who had so aggressively promoted the song, was another. The third was Russ Fratto, a man he'd never heard of. Trading credit for airplay, known as payola, was a common practice at the time, especially when the song was by a black artist. And Berry didn't ask any questions. After all, his first royalty check for "Maybellene" had been more than twice what he'd paid for his house. It was only later that he learned sharing songwriting credits also meant sharing the song's earnings. While there's no doubt Freed's promotion of "Maybellene" was crucial to its success nationwide, Berry fought for years to recover the full rights to the song. "I didn't even know that you could use lawyers to correct these things, you know, then, you know," Mr. Berry says. "So it goes on and on and on, but that happens to rookies, if you want to call a new musician a rookie." In 1986, more than 30 years after he wrote "Maybellene," Chuck Berry was finally credited as the song's sole composer. By that time, it was little more than a legal technicality, but in the end, it may be the most fitting tribute. After all, "Maybellene" could have been written by no one but Chuck Berry. If that's not already obvious from the music and the lyrics, just listen to the guitar solo. The rock 'n' roll guitar was supposed to be a rhythm instrument, polite and unobtrusive, but a little over a minute into "Maybellene," Chuck Berry, wielding his yellow Gibson ES-350T, shattered that image forever. In the years following "Maybellene," Chuck Berry produced an astonishing string of hits: "Roll Over Beethoven," "School Days," "Sweet Little Sixteen," "Johnny B. Goode," to name just a few, more or less inventing rock 'n' roll as he went along. That's pretty much the consensus; everyone from The Beatles to The Rolling Stones has said it. But the man himself takes exception to any claims of paternity. "If you did start something, how can you say that anybody else had anything to do with it? If you started it, you know, you're the--Is that what they say?--the father of rock. Boy, they have no idea how wrong they are." In 1972, 17 years and more than 200 recordings after "Maybellene," Chuck Berry finally scored a number-one hit on the pop charts. The song? A rather indelicate ditty called "My Ding-A-Ling."

Play NPR article with accompaniment

Mabellene

Baby Doll

School Days

Johnny B.

Goode

Rock & Roll

Music

Little Queenie

Roll Over

Beethoven

No Partic

Place to Go

You Cant

Catch Me